VIEWS: 2359

November 4, 2020October Online Event Explored Impacts of Domestic Violence on Children

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began earlier this year, law enforcement agencies across the United States report that incidents of domestic violence have increased by 35%. October is Domestic Violence Awareness Month, so it was a good opportunity for the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community’s Social Services Department to help educate the Community.

In a Zoom meeting titled “The Impacts of Domestic Violence on Children”, held on October 15, SRPMIC members were invited to learn about how to respond to children who have witnessed and experienced domestic violence.

The virtual workshop was presented by Durina Keyonnie, Family Advocacy Center Trauma Therapist; Social Services Manager (CPS) Landon Goodwell; and Master Social Work Intern Arlena Moreno. They discussed how to respond to children who have witnessed domestic violence, trauma and the brain, how children respond when witnessing domestic violence, important factors to keep in mind as a caregiver, and how caregivers can support children after experiencing a traumatic event.

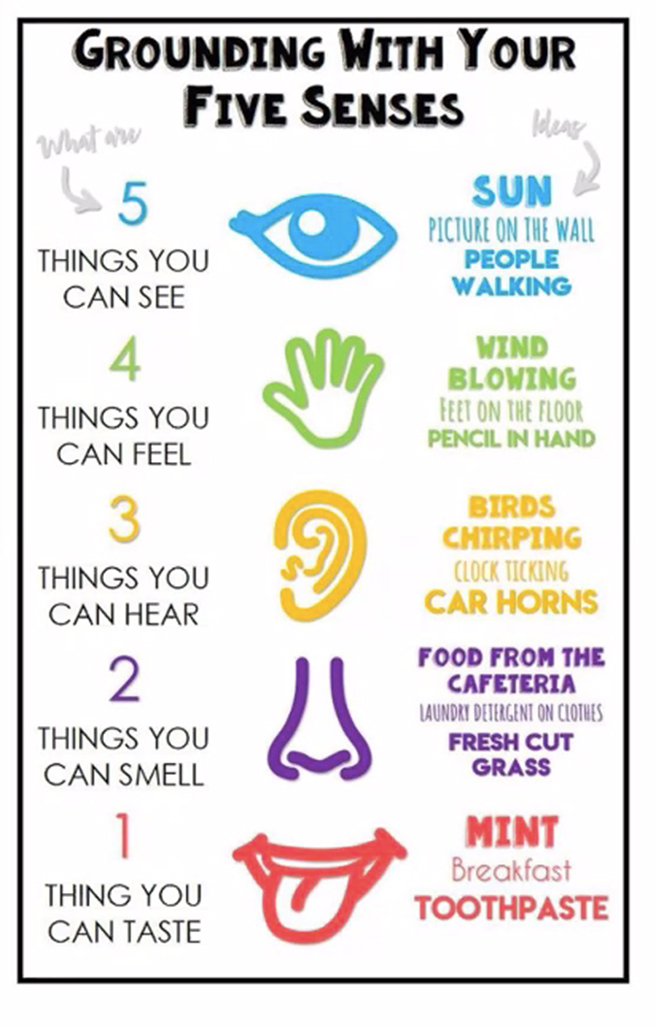

The event started out with a grounding technique, by using the five senses (see photo). This technique will help children and adults who may be feeling angry or sad; help calm children who have a lot of energy; and help decrease their anxiety.

Goodwell provided an overview on what domestic violence can look like. Domestic abuse can come in all shapes and sizes, explained Goodwell:

• Emotional abuse—Talking down to each other and using words as power against another person in our relationships.

• Financial abuse—Controlling all the money and not allowing your partner to make financial decisions or access the bank account.

• Physical abuse—Hitting and punching, burns.

• Cultural abuse—Not allowing your partner to attend cultural activities such as powwows because you don’t want them around other people.

• Sexual abuse—Using sex as a form of control over the other person or assaulting them when they don’t consent.

• Manipulating the children—Using them against one another or using them as bargaining tools.

• Digital/social media—Controlling with whom they are allowed to connect on social media and what they are allowed to post.

“Families with domestic violence within their homes are two times more likely to have a substantiated case of child abuse compared to families without domestic violence,” said Goodwell. “A lot of time the violence spills over to the children, and [we] now have cases of child abuse. It could be emotional, physical, sexual—it could be any number of things that involve children.”

According to Goodwell, witnessing domestic violence can mean seeing actual events of physical or sexual abuse, hearing threats being made, and observing the consequences of abuse, such as scars, bruises, broken household items and blood.

Trauma and the Brain

Being a witness to domestic violence can lead to trauma which can affect the brain. Adults can experience memories of being a witness to domestic violence as a child and become upset, angry and sad about what they experienced. Worse, the children could grow into adults who continue those same abusive actions in their own families.

Keyonnie explained how a child’s brain reacts to witnessing scary events such as domestic violence.

“The hippocampus is like our library inside our brains. [A past] event [can] keep coming up because it’s stored in our brain, and as an adult there are different memories that come up from our childhood,” said Keyonnie. “The prefrontal cortex in our brain helps us do rational thinking and also helps us think logically. The amygdala is a very important part of our brain; it starts to fire up in our brain and is in response mode. The prefrontal cortex then becomes confused and [we are] not able to think clearly and articulate. Trauma in the brain does not discriminate; those three parts of the brain connect with each other.”

Fight, Flight or Freeze

When children see domestic violence in the home, their first reaction may be to run away, attack the abuser or freeze up.

“With fight and flight, the child may feel agitated, angry, overwhelmed, have racing thoughts, or be thinking too fast of how to prevent a situation from happening. They child might try to fight the abuser to protect their mom from being abused,” said Moreno. “Freeze is when a child is hiding. When there is a domestic violence situation in the home they may freeze and struggle about what they should do, and some children go and hide.”

Effects of Domestic Violence on Children

Moreno went over the color wheel that showed the effects of domestic violence mentally, spiritually, emotionally and physically.

• Mentally, a child can feel responsible for what’s happening, have difficulty concentrating in school, develop negative thoughts about themselves and believe that violence is okay.

• Spiritually, they can feel unworthy, hopeless, confused, unmotivated and powerless.

• Emotionally, the child can feel guilt and shame, anger, depression/anxiety, grief/loss, fear of doing wrong, fear of expressing feelings and low self-esteem.

• Physically, a child can regress to earlier stages of development, mimic the abuser’s abusive behaviors, fear for their physical safety, have inability to develop social skills, not react to pain, or experience bedwetting or nightmares.

How Caregivers Can Provide Support

Caregivers can provide the child with verbal reassurance, telling them that these events are not their fault. “As adults, it’s our responsibility to let them know it’s not their fault,” said Keyonnie.

Other verbal reassurance phrases include:

“I will take care of you as best as I can.”

“I love you no matter what.”

“I will help you feel as safe as possible.”

“Violence is not okay.”

What if a Child Tells You He Lives in a Violent Home?

First let the child know you believe in them and that it’s not their fault; give that reassurance, explained Goodwell.

“Allow the child to talk about what’s worrying them, let them get it out. Help the child learn ways to deal with their feelings, help them with those healthy coping skills,” said Goodwell. “Help them create a safety plan for an emergency to get a step ahead of their concerns in their home. Help them feel good about themselves, celebrate them, and talk to them. Do what you can do to help that child out and let the child know you will give their caregiver help, to give that child a little relief.”